Archaeologists have unearthed a diverse array of artifacts at Türkmen-Karahöyük, a site believed to be a possible second capital of the Hittites.

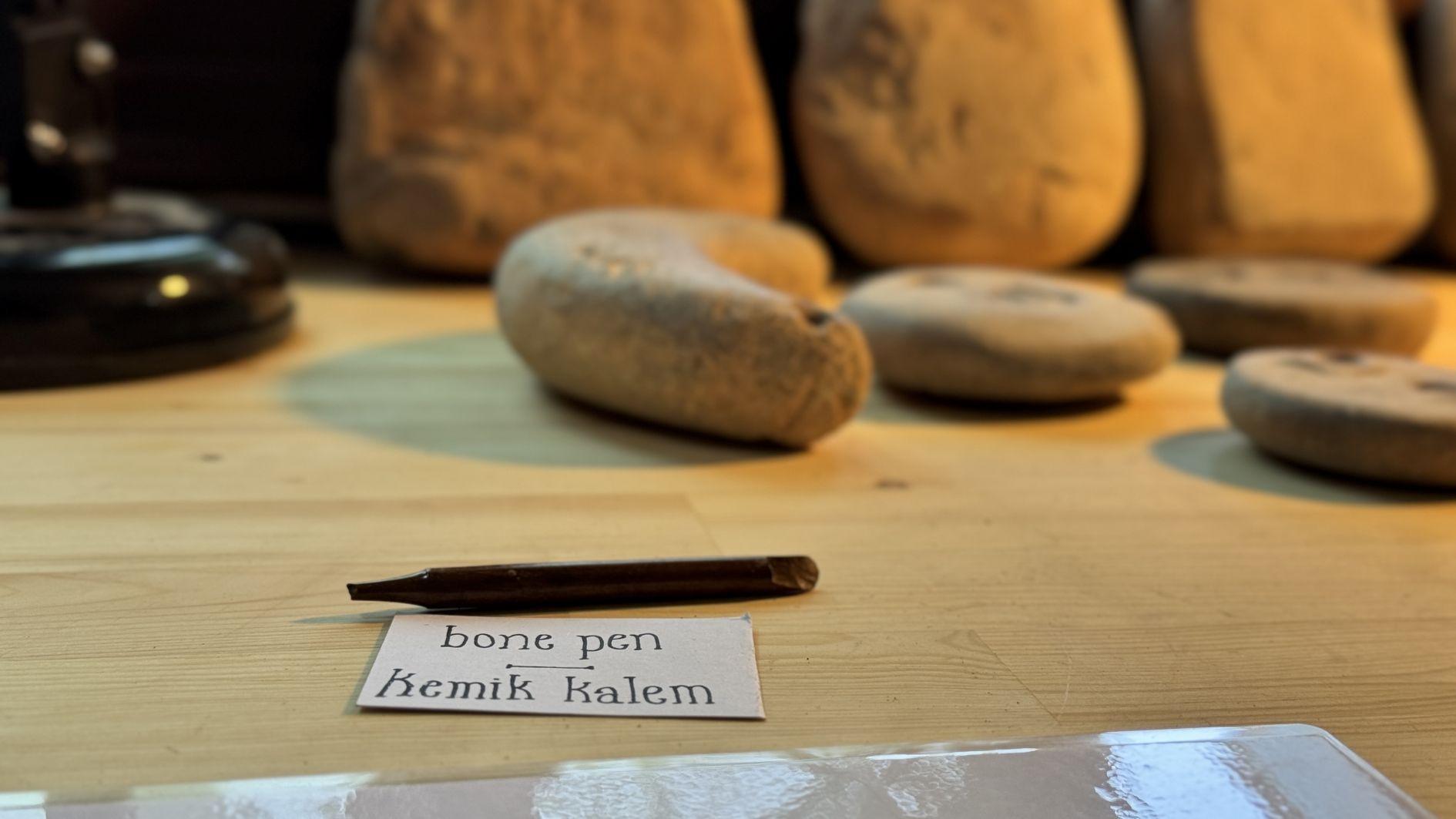

During the excavation that began a year ago, a pen made from animal bone dating back 2,000 years, an arrowhead from 50 B.C., a 1,700-year-old die, a 2,200-year-old bathtub, as well as wheat and barley preserved for 3,000 years, among many other artifacts, have come to light.

Stressing about the significance of the site, excavation co-chair Associate Professor Michele Rüzgar Massa said, “We see that this was an important political and trade center. We found many administrative tools. Among them were a 2,000-year-old animal bone pen and several 4,000-year-old seals. These are believed to have been used by government officials.”

Türkmen-Karahöyük is seen as a strong candidate for the long-lost Hittite capital that served as the empire’s seat some 3,300 years ago. Scholars also believe it may have been the capital of Hartapu, an Anatolian king who lived 2,800 years ago and was a contemporary of the Phrygians.

This season’s excavations yielded numerous ceramics, perfume bottles, jewelry, as well as a 2,000-year-old animal bone pen, arrowheads from 50 B.C., a 1,700-year-old die and a 2,200-year-old bathtub.

Massa noted that they had even come across remains of monkeys once gifted by Egyptian rulers 3,700 years ago.

“This mound is known as the largest single city prior to Konya. We obtained very important results this year. We see that it was a major political and trade center. We found many tools related to governance, including a 2,000-year-old bone pen and several 4,000-year-old seals believed to have been used by officials. This city survived for 3,000 years, with connections stretching from Egypt to Cyprus and the Black Sea. We uncovered fine ceramics, exotic fruits and remains of exotic animals such as monkeys. We also saw evidence of a palace, although we have not yet found it. Signs of burning and arrowheads suggest the city suffered an attack,” he said.

Osborne noted that they had unearthed many Hittite-era structures. “This mound is one of the largest in Türkiye. The buildings here date back to the late Hellenistic period. Around 50 B.C., there was great destruction — burned walls, mudbricks and earth. This was not accidental. This year, we found an arrowhead in the burned layers, indicating the destruction came from an attack. Afterward, the government center moved from here to Konya. This was a significant Hittite city. We found many Hittite buildings, and between 1300 and 1200 B.C., there is a strong possibility that this was the kingdom’s second capital,” he said.