Mehmet Ali Birand: The gracious face of Turkish journalism

Özgün Özçer ISTANBUL - Hürriyet Daily News

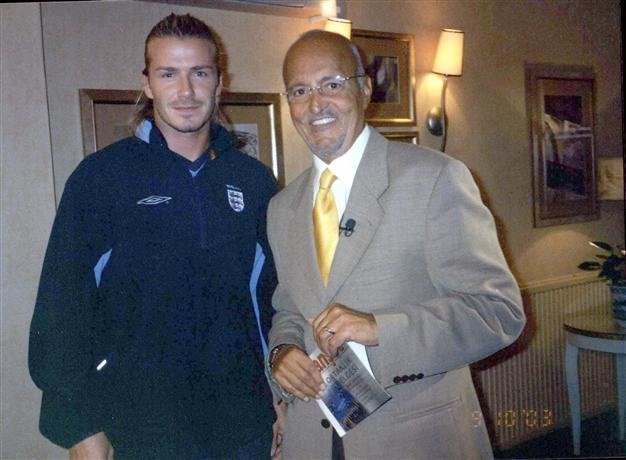

Veteran journalist Mehmet Ali Birand interviewed a number of world-renowned

names, including English football star David

Beckham. AA photo

Turkish journalism is grieving after the abrupt death of its dean and

teacher, Mehmet Ali Birand, following a cardiac arrest at the age of 71.

His inconsumable energy and eternal smile that always emitted

warmth and grace in front of the camera, combined with his work ethic

and rigor, made Birand one of the most beloved and respected

journalistic figures among the public. Birand was also a familiar voice

for

Hürriyet Daily News readers, with his spirited columns in which he felt the pulse of Turkish politics as few commentators could do.

Fellow

news anchors scarcely hid their disbelief in announcing the news of a

man who worked without interruption until he passed away. Birand had, as

usual, presented the main Kanal D news on Jan. 15, passing along his

trademark farewell at the end of the broadcast, “Tomorrow, don’t make an

appointment with anyone else.”

On Jan. 16, he underwent gallbladder surgery (laparoscopic cholecystectomy) at the

American

Hospital in Istanbul in order to replace a stent, while preparing to

broadcast the next day’s edition of “32. gün” (32nd Day), a long-running

news affairs show that had been on the air continuously since 1985.

In

his last column that he wrote from hospital, he expressed his optimism

for the ongoing peace process in Turkey, without neglecting to urge the

government to reopen a

Greek

seminary on Heybeli island that has been shuttered since 1971. However,

the journalist’s heart was unable to cope with what appeared to be a

simple operation, passing away late in the evening of Jan. 17. Birand

had been receiving cancer treatment in 2011 but had refused to slow down

his working pace.

A standard bearer In one

interview, Birand confessed that his biggest fear in life was “being

ordinary.” He need never have worried, as he was a standard bearer for a

profession whose members are still struggling to emancipate themselves.

His greatest trait was doubtlessly his ability to push the limits of

fair reporting in a context of endless political pressure, interrupted

by countless coups and crises. The many programs on which Birand worked

also functioned as an exceptional school, allowing important journalists

such as Can Dündar, Mithat Bereket, Ali Kırca and Çiğdem Anat to get

their feet wet in the journalism profession.

In addition to being

a pioneer of television news broadcasting, he was the first to

interview Abdullah Öcalan, the leader of the outlawed

Kurdistan Workers’ Party

(PKK), in 1988 and also the first to investigate the most significant

political events in Turkey with a series of documentaries: “Demirkırat”

(covering the 1960 military coup), “12 September” (focusing on the 1980

military coup) and “28 February, the last coup” (relating the events

that led to the fall of the Muslim-rooted Welfare Party government in

1997). Birand was reportedly preparing a new documentary for the first

time in years, this once about Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Abdi İpekçi was his masterBorn

on Dec. 9 1941, in Istanbul, Birand lost his father at the age of 2. He

would say of his mother, Mürvet, “She was my father and my sister, she

was everything to me.” During his childhood, he had to overcome a number

of health issues. Despite his family’s economic difficulties, he was

able to enroll in the renowned

Galatasaray

High School but couldn’t finish his studies at Istanbul University.

This event would be a defining moment of his life because, in 1964, he

started to work at daily Milliyet thanks to the offices of

journalist

Abdi İpekçi, whom he would call his “master,” along with Sami Kohen.

İpekçi, meanwhile, was assassinated by ultranationalist Mehmet Ali Ağca

in 1979.

“Until going to Galatasaray, I had no idea what I wanted

to become. During high school, I started to consider journalism. I used

to see journalism as a sheep raising its head in the herd – a sheep

which raises its head and says something among the millions of them,”

Birand would say about this period of his life. Milliyet was also the

place where he met his life partner, Cemre. The couple married in 1971

and had one son, Umur.

In 1972, he moved to Brussels to become his newspaper’s

Europe

correspondent but would become the editor-in-chief of Milliyet for a

short period after İpekçi’s murder. Birand, however, would achieve true

recognition with “32nd Day” in 1985. He used to travel from Brussels to

Ankara

for his monthly show on the public broadcaster TRT. He interviewed a

number of Turkish and foreign personalities, such as former USSR leader

Mikhail Gorbachev, former

French President François Mitterrand and legendary British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the “iron lady.”

He took a big risk by interviewing Öcalan in 1988, during a time when the largely unknown

PKK

leader had yet to become a figure of such public revulsion in parts of

Turkey. The interview cost him the establishment’s support, and he had

to face many trials over the years. Despite the pressure, he returned to

Turkey permanently in 1991; the following year, he moved his program to

the private broadcaster Show TV. But he faced pressure again after the

political events of Feb. 28, 1997, for his dissident stance and was

consequently forced to leave. In 1997, he started to work at the newly

founded broadcaster CNN Turk. He had also been presenting the evening

news program at Kanal D since 2005.

Birand never denied his love

for the small screen. He would say of his outstanding communication

with the audience, “I have the ability to simplify things that look

complicated. I have always put myself in the shoes of those who are

watching me. I reacted like them. And people liked it.”

“The camera

always reveals what’s artificial,” he said on another occasion. Turkish

society will greatly miss his authenticity.