Rashomon, the Eurozone crisis and Turkey

Andrew

Lo, professor of finance at MIT, likened the different financial crisis

narratives to Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon when he recently reviewed 21 books

about the financial crisis.

In

the movie, a crime is recounted differently by each protagonist. Lo argued that

there are “several mutually inconclusive narratives” of the 2008-2009 crisis. Similarly,

there are two distinct tales of the Eurozone crisis.

According

to the German version of the story, fiscal profligacy is the culprit, and

therefore austerity the cure. Moreover, fiscal restraint will restore markets’

confidence. Just look at how well Latvia and Ireland, two countries that

swallowed their painful pills, are doing!

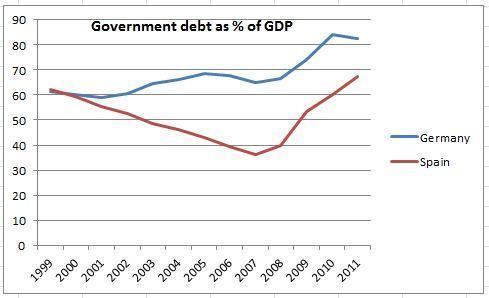

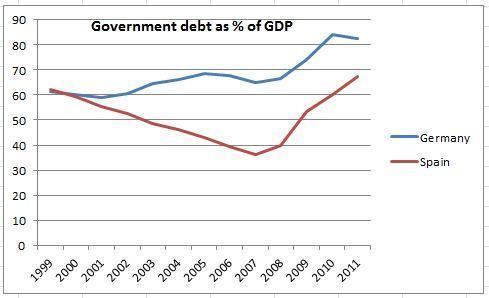

Nobel

laureate Paul Krugman, professor of economics at Princeton and columnist for

the New York Times, disputes this narrative. He first notes that Spain’s

government debt to GDP ratio was actually declining from 1999 until the crisis,

whereas Germany’s was creeping up.

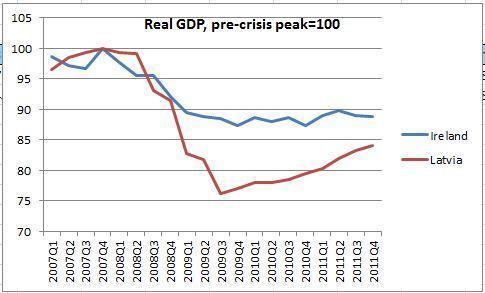

As

for the two poster children, Ireland and Latvia’s GDPs are still significantly

below pre-crisis levels. To add insult to injury, Ireland's credit

default swaps, which provide insurance against the country's not paying its

debt, are more than twice Turkey’s and imply an annual probability of default

of nearly 8 percent.

This

narrative is not without holes: Spain’s problem was not fiscal but private sector

profligacy, led by housing. And the German argument holds much better for

Greece. But Krugman is right that markets

are definitely not rewarding austerity. Besides, I have yet to meet this

famous “confidence fairy”.

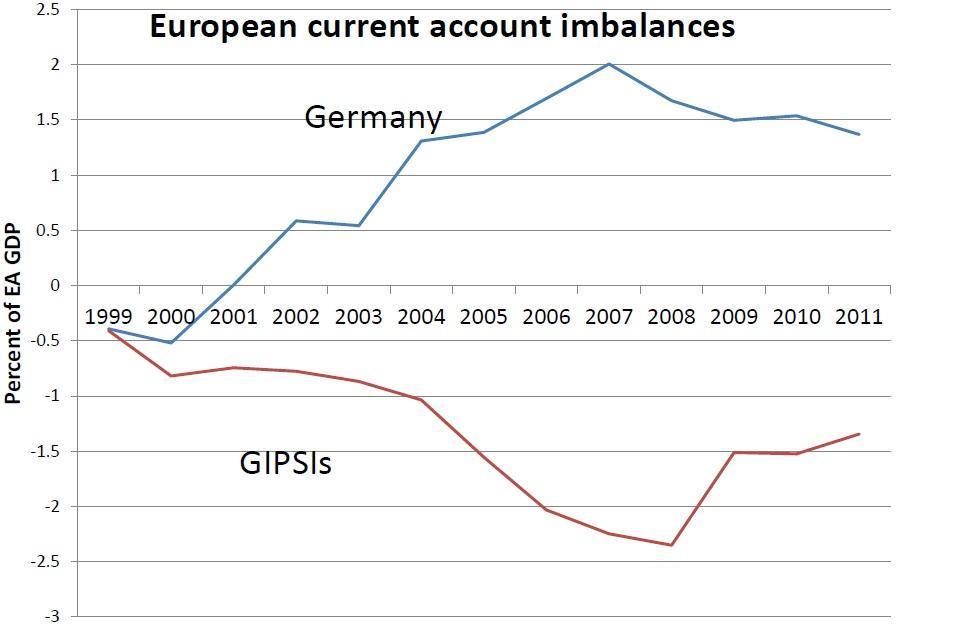

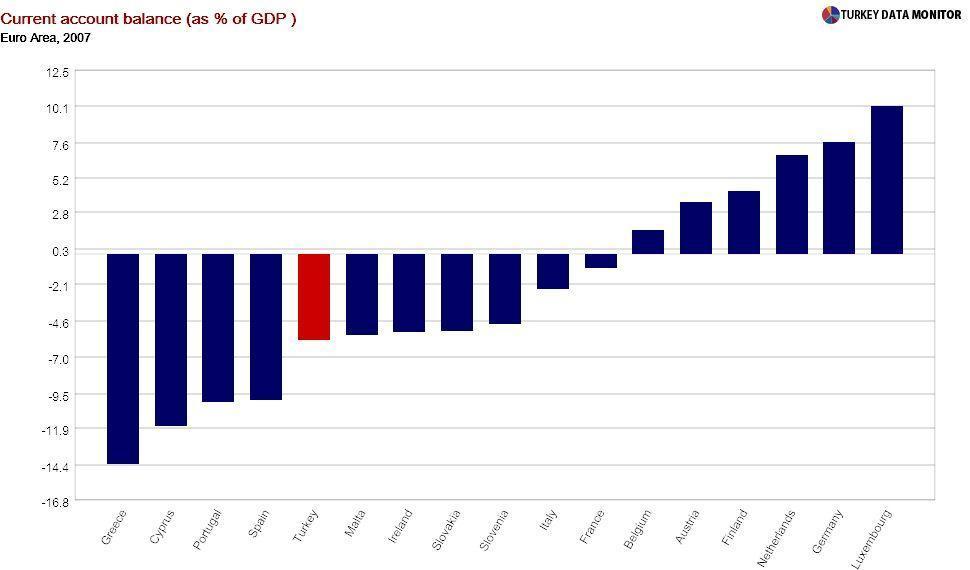

In

any case, I would agree with Krugman that Europe’s main problem is balance of

payments. Germany’s current account surpluses were matched by the deficits of

Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Ireland, collectively known as the GIPSIs.

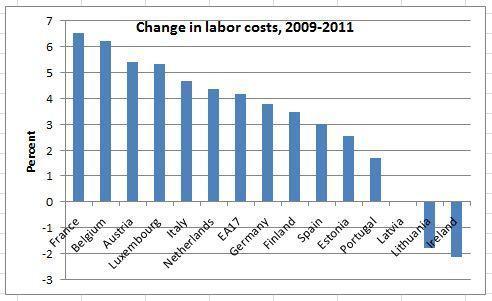

Concurrently,

there were huge capital flows to the GIPSIs, which were the driving force

behind the public or private spending binges. This was fine as long as the

music kept playing, but once it did stop, these countries could not use the

exchange rate for adjustment and had to resort to internal devaluation, i.e. painful

wage cuts.

How

does Turkey fit in all this? For one thing, Turkish policymakers are firmly sticking

with the German narrative. For example, economy tsar Ali Babacan’s speech at

the Istanbul

Finance Center conference last week could have easily come from Deutsche

Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann.

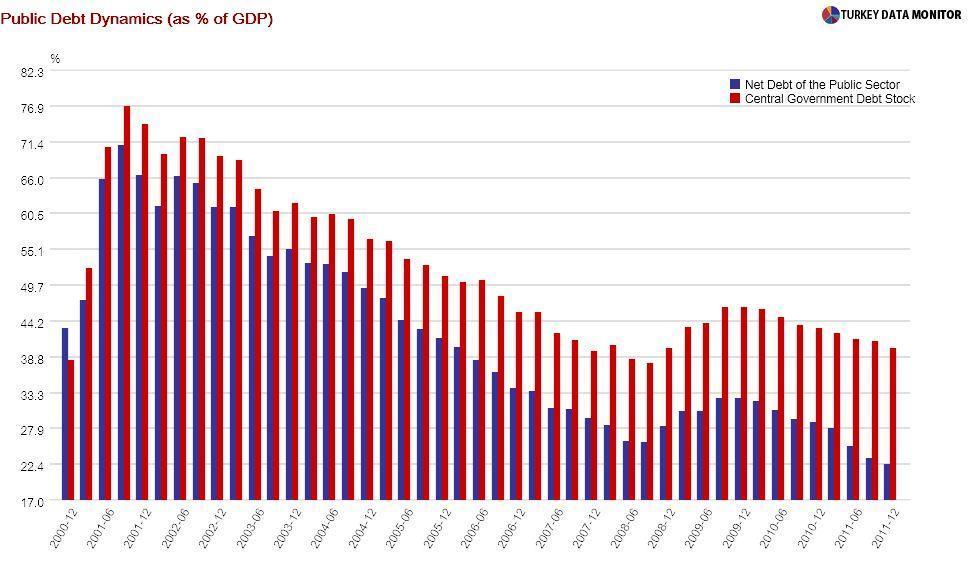

But

maybe this adherence reflects realpolitik more than anything else. With a debt

to GDP ratio of 40 percent at the end of 2011, Turkey looks like the real

poster child for austerity, even though the IMF has recently

warned that budget balances are not as strong as they look.

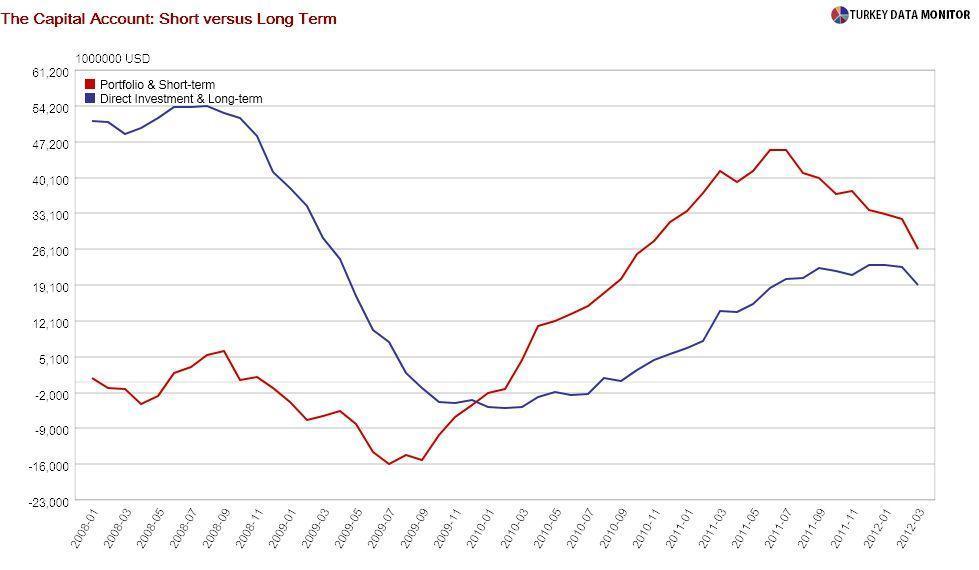

More

importantly, once you subscribe to the Krugman narrative, you may suddenly

notice that Turkey’s current account deficit of 10 percent of GDP is comparable

to the GIPSIs’ levels before the crisis. Moreover, that deficit is still

financed by short-term capital flows, as Friday’s March

figures confirmed.

Unlike

the GIPSIs, Turkey can use the exchange rate and monetary policy as adjustment

mechanisms, but you just wouldn’t want to alarm markets.

Graphs 1, 2, 5 and 6 as well as the confidence fairy are from a presentation Paul Krugman gave in Brussels on Thursday.