Demystifying Turkish UFOs

I can hear you say it: “He finally lost it.” Nope, I have not gone completely nuts. I haven’t smoked anything that would make me see UFOs, either. I am talking about Turkey’s Unidentified Financing Objects.

During the past year, a significant share of Turkey’s large current account deficit has been

financed by NEOs (net errors and omissions, nothing to do with

the Matrix), which is basically an accounting term covering everything in the Balance of Payments that is not measured. This item amounted to $2 billion in July (that figure was later revised down to $1.6 billion), prompting many

to speculate on the sources of these funds.

Some believe NEOs reflect

capital flight from Iraq and Syria, and more recently from Russia and Ukraine. Others have resorted to conspiracy theories, claiming the mystery funds could be from Gulf States. Even though official flows to Turkey from his country are

very small, the Kuwaiti ambassador recently

threatened that the deportation of his country’s military attaché, who had been involved in a

road rage incident, would negatively influence his country’s investment.

Despite my

occasional pieces of

investigative journalism, my reporter

friends do not accept me as one of their own. I will take their word for

it and try to crack this case with my knowledge of statistics. But

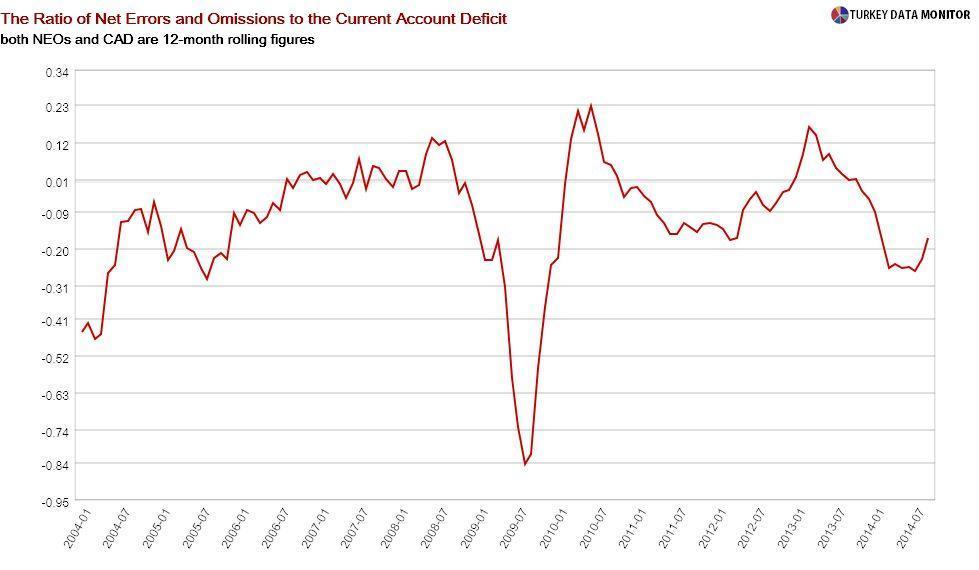

before I go on, I should tell you that NEOs are not new. But whereas

they used to oscillate around $3 billion inflows or outflows (on an

annual basis) before 2008, there were $8 billion unidentified outflows

in early 2013 and $15 billion inflows a year later.

But Turkey’s

current account deficit surged in this period, so we should compare NEOs

to the current account. There were several episodes during the last two

decades when the ratio of NEOs to the current account was much higher

than today. The huge unidentified outflows in 1998 were eventually

linked to shuttle trade, and once the Central Bank estimated it, NEOs

normalized. There could be a similar measurement problem today.

More recently, almost the entire deficit was financed by NEOs in 2009. In two separate reports in

2011 and

2012, the Central Bank argued that locals hoard foreign currency aboard, which they tap into during times of stress. The Bank started updating its statistics with data from the

Bank of International Settlements in 2009, but I do not think that dataset would include all of the deposits abroad. And I have yet to figure out how money transfers would not get caught.

I decided to test these theories officially. As a proxy for

mismeasurement of trade statistics, I compared official Turkish figures with data from the IMF’s Direction of Trade statistics. I have been suspecting that tourism revenues may be underreported, so I included the change in seasonally-adjusted tourism revenues in my model. Finally, I tested the Central Bank’s explanation by adding in changes in capital flows.

This simple framework does a remarkable job in explaining UFOs. However, NEOs did turn out to be much higher than what the model would predict in certain periods, mostly during the last three years. Therefore, while I cannot rule out the conspiracy theories, my analysis suggests that there is a much less sinister explanation for at least part of the Turkish UFOs.

I can hear you say it: “He finally lost it.” Nope, I have not gone completely nuts. I haven’t smoked anything that would make me see UFOs, either. I am talking about Turkey’s Unidentified Financing Objects.

I can hear you say it: “He finally lost it.” Nope, I have not gone completely nuts. I haven’t smoked anything that would make me see UFOs, either. I am talking about Turkey’s Unidentified Financing Objects.